Twenty years ago, Zhongguancun was but farming fields and small houses, far from the city center of Beijing. The ‘cun’ at the end of Zhongguancun literally means “village.” As with much else in China, the change has come lightening fast.

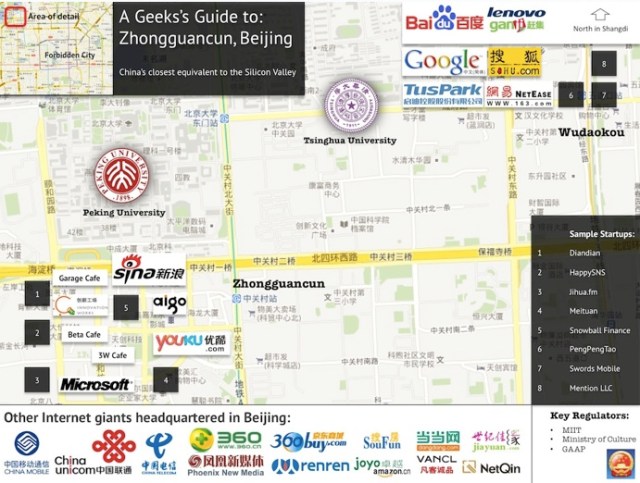

Today, Zhongguancun is China’s closest equivalent to Silicon Valley. It’s host to electronics super malls, research centers, publicly-listed tech giants, and hundreds of startups. During my walk to work between twenty-story office towers, it’s hard to imagine this land was farmed but one short generation ago.

Here are three reasons why Zhongguancun (or the larger Haidian district) has grown into China’s top tech hub:

1) Academic Hub

Right next door are China’s top two universities, Peking University and Tsinghua University. But the northwest of Beijing is also home to countless other universities, including technical universities like USTB, BIT, BUPT, and Beihang. It’s the raw talent pool that has American industry leaders and politicians bemoaning a new “engineering gap.”

The transition from farming village to technology hub began with technology research. In addition to the universities, funding came from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and later multinational corporations (MNCs). As Daniel Shi notes on Quora, “There is just a ridiculous number of MNCs with their R&D centers in Beijing: Nokia, Ericsson, Motorola, Sony Ericsson, Microsoft, IBM, Sun, Oracle, BEA, Alcatel Lucent, Google. Nowhere in the US do you have such a huge concentration of R&D organizations in one city.”

Soon, a small market emerged in Zhongguancun to sell electronics to students and academics. Jack Xu, founder of lite-blog Diandian, describes a serendipitous meeting in that scene:

2) Government and Media

In America, an entrepreneur hears “government” and runs the other way. In China, government is best kept close, out of choice or necessity. The Internet is one of the most private of industries in China, one of the few without huge state-owned firms, but the government still plays a key role.

At the early stage it can be government contracts, subsidized office space in a tech park, or financing from a government-affiliated research institution. The government wants to build Beijing as a showcase capital in all aspects, so there’s extra funding for tech too.

Once a startup reaches scale, government connections are key to everything from payment licenses to “content management.” When your video website is blocked because it was found to contain sensitive political or pornographic content, who you gonna call?

Virtually all business in China is of “strategic national interest,” but some is extra-strategic. All media firms or even sites with user-generated content must have a big presence, if not their headquarters, in Beijing.

3) A Virtuous Cycle

A tech hub can build momentum that feeds upon itself. Startup founders come out of research centers and large technology firms, drawing upon their network for advice, seed funding, and talented employees. When the boss leaves to launch his own venture, it’s common for half of his division—the talented half—to go with him. The employee networks of Beijing-based tech giants like Baidu, Sohu, and Sina are becoming Chinese versions of the “PayPal Mafia.”

In “Why Startup Hubs Work,” Paul Graham of Y-Combinator writes, “I think there are two components to the antidote: being in a place where startups are the cool thing to do, and chance meetings with people who can help you. And what drives them both is the number of startup people around you.” Like Silicon Valley, Zhongguancun also has a critical mass of people who are crazy enough to do startups.

Hangzhou is home to the Alibaba Group and its e-commerge empire (Taobao, TMall, Alipay, and Alibaba.com). Neighboring Shanghai is rich in gaming, MNCs, and venture capitalists, although they fly up to Beijing to do most of their deals. As far as tech hubs, this area is second after Beijing.

Shenzhen is the headquarters of Tencent, China’s largest social networking and gaming company. Equally impressive is the hardware hacking coming out of the region. It’s home to countless entrepreneurial Shanzhai electronics manufacturers who copy, mix-and-mash, to create ”Motoloba” handsets and “commemorative” Steve Jobs Android tablets. When you hear about “sub-$100 Chinese-flavored Android devices”, it’s Shenzhen leading the charge.

Other up-and-coming hubs include Dalian, Chengdu, and Xi’an,

Beijing is an acquired taste, one that’s often smoky with pollution. In a Sinica Podcast discussing the soul of Beijing, China hand Jeremy Goldkorn of the blog Danwei.org called it “the anti-lifestyle capital, the anti-San Francisco.” The unpleasantness of the city, the lack of Shanghai’s creature comforts or Shenzhen’s sunshine, gives it an edge. There’s a gritty determination to seize the moment, whatever the obstacles in the way.

One friend told me that Kai-fu Lee was recently asked why his startup incubator InnovationWorks wasn’t based in picturesque Chengdu, where the cost-of-living is low and the ladies are said to be the fairest in all of China. Lee jokingly replied to his entrepreneurs that when they’re happy and relaxed, he’s not.

But do not mistake it for a city of automaton entrepreneurs. Beijing is at once ”the center of authority and a hotbed of creative thinking” as Evan Osnos writes in “City of Dreams.” There are leaps of creativity. Sites that start as copycats evolve to become unrecognizable from the original, like the red-hot microblog Sina Weibo that today bears little resemblance to Twitter.

When TechCrunch held its first international Disrupt Conference, it was right to come to Beijing. It’s dynamic, messy, and very different. But Silicon Valley aside, there’s no better place on earth for tech right now..

Source:http://techcrunch.com/2011/12/27/geeks-guide-china-silicon-valley/

Today, Zhongguancun is China’s closest equivalent to Silicon Valley. It’s host to electronics super malls, research centers, publicly-listed tech giants, and hundreds of startups. During my walk to work between twenty-story office towers, it’s hard to imagine this land was farmed but one short generation ago.

Here are three reasons why Zhongguancun (or the larger Haidian district) has grown into China’s top tech hub:

1) Academic Hub

Right next door are China’s top two universities, Peking University and Tsinghua University. But the northwest of Beijing is also home to countless other universities, including technical universities like USTB, BIT, BUPT, and Beihang. It’s the raw talent pool that has American industry leaders and politicians bemoaning a new “engineering gap.”

The transition from farming village to technology hub began with technology research. In addition to the universities, funding came from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and later multinational corporations (MNCs). As Daniel Shi notes on Quora, “There is just a ridiculous number of MNCs with their R&D centers in Beijing: Nokia, Ericsson, Motorola, Sony Ericsson, Microsoft, IBM, Sun, Oracle, BEA, Alcatel Lucent, Google. Nowhere in the US do you have such a huge concentration of R&D organizations in one city.”

Soon, a small market emerged in Zhongguancun to sell electronics to students and academics. Jack Xu, founder of lite-blog Diandian, describes a serendipitous meeting in that scene:

In 1997, Zhongguancun Technology Park was a tiny village. It had only two buildings, and an assortment of entrepreneurs hustling their programming skills, taking government contracts, and hiring [Tsinghua] students like me to do the work. At times they might get RMB 100,000 for a contract, but pay us only RMB 5000, thus retaining 95% for themselves. Back then I could make a mere RMB 2000 a month, 1000 for myself and 1000 for my parents, so they wouldn’t need to farm anymore. To me, it was a responsibility, to survive on my own as early as possible. It was also because of my work in Zhonguancun that I became a well-known programmer in a small circle and later a real opportunity came along.That real opportunity was Jack Xu’s meeting with Joseph Chen in 1998. Today, Chen is the CEO of the social network Renren (NYSE: RENN), where Xu worked for five years, including as VP of the Interactive Division.

2) Government and Media

In America, an entrepreneur hears “government” and runs the other way. In China, government is best kept close, out of choice or necessity. The Internet is one of the most private of industries in China, one of the few without huge state-owned firms, but the government still plays a key role.

At the early stage it can be government contracts, subsidized office space in a tech park, or financing from a government-affiliated research institution. The government wants to build Beijing as a showcase capital in all aspects, so there’s extra funding for tech too.

Once a startup reaches scale, government connections are key to everything from payment licenses to “content management.” When your video website is blocked because it was found to contain sensitive political or pornographic content, who you gonna call?

Virtually all business in China is of “strategic national interest,” but some is extra-strategic. All media firms or even sites with user-generated content must have a big presence, if not their headquarters, in Beijing.

3) A Virtuous Cycle

A tech hub can build momentum that feeds upon itself. Startup founders come out of research centers and large technology firms, drawing upon their network for advice, seed funding, and talented employees. When the boss leaves to launch his own venture, it’s common for half of his division—the talented half—to go with him. The employee networks of Beijing-based tech giants like Baidu, Sohu, and Sina are becoming Chinese versions of the “PayPal Mafia.”

In “Why Startup Hubs Work,” Paul Graham of Y-Combinator writes, “I think there are two components to the antidote: being in a place where startups are the cool thing to do, and chance meetings with people who can help you. And what drives them both is the number of startup people around you.” Like Silicon Valley, Zhongguancun also has a critical mass of people who are crazy enough to do startups.

BEYOND BEIJING

I wrote that Zhongguancun is China’s closest equivalent of Silicon Valley. The caveat is because there’s a lot happening elsewhere in China too. China’s three Internet giants are Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent, but only search giant Baidu is headquartered in Beijing.Hangzhou is home to the Alibaba Group and its e-commerge empire (Taobao, TMall, Alipay, and Alibaba.com). Neighboring Shanghai is rich in gaming, MNCs, and venture capitalists, although they fly up to Beijing to do most of their deals. As far as tech hubs, this area is second after Beijing.

Shenzhen is the headquarters of Tencent, China’s largest social networking and gaming company. Equally impressive is the hardware hacking coming out of the region. It’s home to countless entrepreneurial Shanzhai electronics manufacturers who copy, mix-and-mash, to create ”Motoloba” handsets and “commemorative” Steve Jobs Android tablets. When you hear about “sub-$100 Chinese-flavored Android devices”, it’s Shenzhen leading the charge.

Other up-and-coming hubs include Dalian, Chengdu, and Xi’an,

THE EDGE

Silicon Valley is often said to draw top talent because it has one of the best living environments on earth. No one would say that about Beijing.Beijing is an acquired taste, one that’s often smoky with pollution. In a Sinica Podcast discussing the soul of Beijing, China hand Jeremy Goldkorn of the blog Danwei.org called it “the anti-lifestyle capital, the anti-San Francisco.” The unpleasantness of the city, the lack of Shanghai’s creature comforts or Shenzhen’s sunshine, gives it an edge. There’s a gritty determination to seize the moment, whatever the obstacles in the way.

One friend told me that Kai-fu Lee was recently asked why his startup incubator InnovationWorks wasn’t based in picturesque Chengdu, where the cost-of-living is low and the ladies are said to be the fairest in all of China. Lee jokingly replied to his entrepreneurs that when they’re happy and relaxed, he’s not.

But do not mistake it for a city of automaton entrepreneurs. Beijing is at once ”the center of authority and a hotbed of creative thinking” as Evan Osnos writes in “City of Dreams.” There are leaps of creativity. Sites that start as copycats evolve to become unrecognizable from the original, like the red-hot microblog Sina Weibo that today bears little resemblance to Twitter.

When TechCrunch held its first international Disrupt Conference, it was right to come to Beijing. It’s dynamic, messy, and very different. But Silicon Valley aside, there’s no better place on earth for tech right now..

Source:http://techcrunch.com/2011/12/27/geeks-guide-china-silicon-valley/

No comments:

Post a Comment